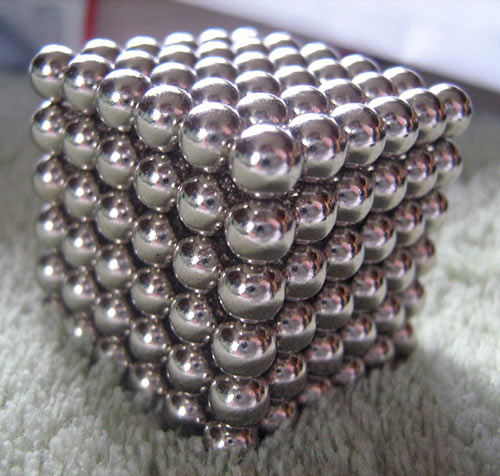

A commenter on this post pointed to this new ban, in the Australian State of Victoria, on bundles of little rare-earth magnets...

...sold as constuction toys.

A few years ago, when these branded collections of spherical (and now also cubic) magnets were first gaining popularity, one of the sellers of such things noticed I'd written this, this, and this (and possibly they also noticed this), or just that I'm pretty high in the results for a Google search for rare-earth magnets. They offered to send me some of their "jewellery magnets", from which you can make bracelets and rings and uncomfortable earrings and so on, for review.

I said it looked as if the more complex shapes would be fiendishly difficult to create without all the magnets clicking together into a blob all the time, and asked if this was a problem.

They didn't reply. Or send me a free infuriating blob of magnets.

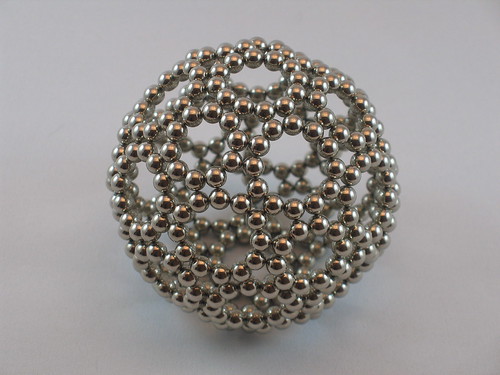

(Years ago, Mark picked up my Amazing Magnets ball and squished it into a coagulated impossible lump. I left it that way. It took Alan, whose lot in life it is to protect the world from the entropic influence of people like me and Mark, ages to reconstruct it.)

That constitutes the entirety of my professional involvement in the little-toy-magnets world. Perhaps I was wrong; it's demonstrably possible to make all sorts of nifty things with them:

(Image source: Flickr user IslesPunkFan)

(Image source: Flickr user IslesPunkFan)

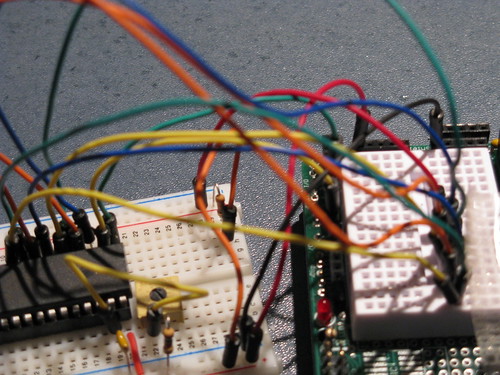

(Image source: Flickr user l0b0)

(Image source: Flickr user Happy Monkey)

Until now.

Toy magnets like these are now banned, in the process of being banned, or at least temporarily withdrawn from sale, in various jurisdictions both here in Australia and elsewhere.

All this excitement has happened because rare-earth magnets are dangerous to swallow.

They're not a poisoning hazard. An alternative name for the ceramic these magnets are made from is "NIB", for neodymium, iron and boron, and those elements are not particularly toxic to mammals individually or in combination. (Calling these things "neodymium magnets" is actually pushing it a bit; it's the neodymium in the formula that allows it to be magnetised so strongly, but the molecule is mostly iron, Nd2Fe14B.) The fragile black ceramic of the magnets themseves is almost always covered with a protective material, usually a plating of shiny nickel, but that's pretty harmless, too.

Swallowing one or more rare-earth magnets in one go is unlikely to do any harm at all. They'll just click together in your mouth or stomach, and probably pass through your gut without complications; even the block-shaped ones have rounded corners.

But if you swallow one or more magnets, then wait for them to move down your gut a bit, then swallow another magnet or three, the separate magnets or masses thereof can stick together with some of your tissue in between. This is likely to be Bad News.

(You can probably do something similar if you inhale one magnet after another, too. The above-linked medical literature also notes that a kid who's swallowed only one rare-earth magnet, and then goes in for magnetic resonance imaging, can find himself in a world of pain.)

These problems are not actually a new thing. As the New York Times points out, previous rare-earth-magnet construction toys have also been withdrawn, for the same reason.

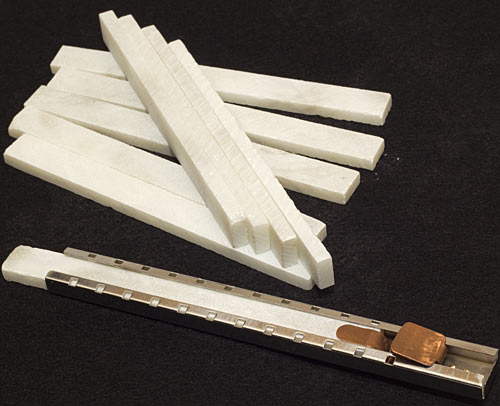

(Image source: Flickr user Karl Horton)

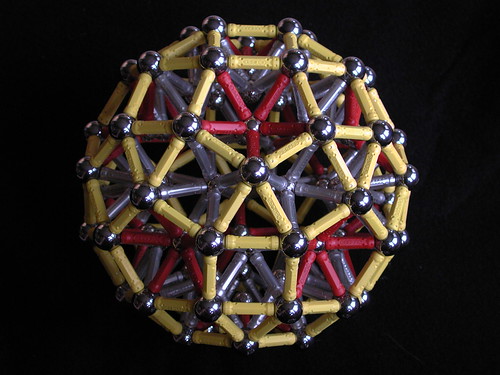

These toys first hit the big time with "Geomag"...

(Image source: Flickr user aldoaldoz)

...which is based around plastic pieces with small rare-earth magnets on their ends and corners. And Geomag wasn't an original idea, either; people had been making sculptures out of rare-earth magnets and steel balls for years (q.v. that Amazing Magnets ball, which I reviewed in 2002).

"Roger's Connection"...

(Image source: Flickr user IslesPunkFan)

...came out a couple of years before Geomag. It has much longer rods, and larger magnets recessed into the ends of the rods for a less wobbly connection. I bought a couple of sets years ago, and they're still on sale today, though perhaps not for much longer.

Geomag was the first really popular rare-earth-magnet construction toy, though, and it spawned umpteen cut-price competitors.

You can lever or chew the magnets out of the ends of Geomag-type components (or, for advanced experimenters...

(Image source: Flickr user Windell Oskay, one of the Evil Mad Scientists)

...dissolve the rods in acetone), and the magnets will just fall out of some of the really cheap and nasty Geomag knockoffs. And a child that eats one, waits a while and then eats another, may end up grievously injured.

"Magnetix" was the biggest Geomag knockoff brand and far from the worst-made, and it was withdrawn from sale in the USA after loose magnets killed one kid and put a few others in surgery.

Over the same period of time, bicycles killed, maimed and paralysed far, far more children, of course. But that doesn't make it OK to sell toys with small parts that fall off, even if those small parts don't have the ability to give you bowel ischemia via quantum physics.

The people who sell little round-or-square magnets under brands like...

...Buckyballs or Zen Magnets don't contest any of this. They've also previously cooperated with regulatory bodies by improving their safety warnings and complying with the usual bureaucratic labelling-law friction, like when Buckyballs said their toy magnets were suitable for children aged 13 and up, when existing local law said they only actually meet the requirements for 14 and up.

But now the magnet-sellers are being sued by the US Consumer Product Safety Commission, and have responded with...

...a "Save Our Balls!" campaign, and a petition, and so on.

Their argument is pretty straightforward: There are many things which, when left unattended, and found and eaten or otherwise interacted with by a toddler, can gravely harm said toddler. Few of these things are banned, because even if humans abandoned civilisation and returned to the trees, there would still be rocks and sharp sticks all over the place.

The CSPC's purpose is to "protect the public from unreasonable risks of injury or death". Their full complaint (PDF here) contends that these magnets do constitute such an unreasonable risk, because no warning on the box or in the instructions can prevent these little magnets from being left stuck to the fridge or on the floor or in some other place where small kids can find them. The CSPC also contends that older children, if they do things like simulating mouth and tongue piercings by putting a magnet on each side, can swallow or inhale the magnets and end up very ill. This has actually happened at least once. (Given the popularity of tongue studs and of these magnet toys, I bet older children have swallowed one or more magnets quite a lot of times. It's only likely to be a problem if they wait a while and do it again.)

I think the most important part of the CSPC complaint, though, and the part which raises it above mere Think Of The Children busybody nonsense, is that consumers demonstrably do not recognise the risk posed by toy-magnet products.

The CSPC are not complaining about knives, and saucepans full of boiling water, and automobiles, all of which harm and kill far more children per year than little magnets do, because it is generally recognised that children need to be protected from these things. Most people with toddlers, or even without, would not leave a straight razor taped to the fridge two feet off the ground.

But people haven't gotten a similar message about little magnets.

And it's not a theoretical problem; kids keep eating the damn things.

The CSPC complaint mentions only Buckyball- and Buckycube-branded magnets, but if it's upheld, I think you can can reasonably expect all such magnets to be banned in the USA.

I'm not certain, though. It could just end up banning such magnets when they're sold as novelties or toys.

This seems to be the way it's working out here in Australia. The Western Australian ban does not apply to "magnets used for industrial or scientific purposes"; similar exceptions are made in a 2010 Tasmanian interim ban (PDF here), and in the recent New South Wales interim ban (PDF here).

I'm actually quite heartened by the NSW ban, because it specifically says it only covers magnets "that are intended or marketed by the manufacturer primarily as a manipulative or construction desk toy or as jewellery".

This is still bad news for sellers of brightly-coloured marked-up magnet packs, and still means many ordinary consumers will miss out on being able to pay the premium to buy such items in ordinary consumer outlets, and probably won't be able to find them anywhere else.

But this ban says nothing about people selling un-marked-up magnets, without any statements about their purpose, for rather better prices on eBay and elsewhere.

Spherical magnets seem to be a little thin on the ground on eBay right now. Craft yourself a round-magnet-finding search string and all you'll see are disks and cylinders. I wouldn't be at all surprised if many sellers (overwhelmingly in China, which is where I think all cheap NIB magnets are made) decided to stop listing spherical magnets for a while, in case their products all get seized by Customs wherever they send them, and they then get lots of negative feedback.

If you cease to discriminate by shape, though, it's not hard to find inexpensive "Buckycube"-type cubic magnets.

"Buckycubes" are 4mm NIB cubes in a selection of colours. The cheapest no-name eBay cubes are all plated with silvery nickel, and may have thinner plating (or may not), but very small NIB magnets like these are generally hard-wearing; even the tiny contact points on spherical ones don't wear out that fast. And if they're way cheaper you probably won't care if the nickel flakes off a couple of them.

A 216-piece pack of Buckycubes will set you back $US39.95 + $US5.95 for shipping; 21.25 US cents per cube. To be fair, it'll probably cost you a bit less, since the Buckyballs people are for some reason currently having something of a fire sale, with coupon codes and such. 20% off your whole order seems to be easy to get; if that applies to shipping as well as the item price, then you'll be paying 18.4 cents per cube.

Restrict your eBay search to 4mm cubes, and as I write this you'll find the cheapest 216-piece pack for $US26.39 delivered; that's 12.2 cents per magnet. (Make sure you do a "world" search; local-currency prices in Australia, at least, are a bit higher. It seems that even China can't believe how crappy the US dollar is these days.)

This seems to be about the floor price. If you want a thousand-piece pack, it's $US119.99 delivered, a molecule less than 12 US cents per magnet.

UPDATE: I just noticed that well-known online cheapie-shop DealExtreme is shamelessly selling a set of 216 golden 3mm sphere magnets for $US15.40 delivered to anywhere, 216 5mm black spheres for $US17.10 delivered, and 125 4mm silver cubes for $US16 delivered. These are excellent prices to start with, and there are bulk discounts if you want to buy three or more units. Just don't try to re-sell them, if you live somewhere with these anti-toy-magnet laws!

UPDATE 2: More DealExtreme tiny-magnet sets. If you're a real penny-pincher they'll sell you a hundred minuscule 3-by-1mm discs for only $US4.10, and they have a nicely-packaged 216-3mm-sphere pack for $US15.60. 216 "silver white" 5mm spheres (which really do look silvery rather than just polished-steel-ish) are $US20.30, as are 216 golden 5mm spheres. 216 silver 4mm cubes will set you back $US18.70; 216 5mm cubes in the same finish are $US20.80.

Oh, and here are 216 red 5mm spheres for $US17 delivered!

(And then there's this kit, which only gives you 27 spheres and 36 long rods for $US15.90. But it comes in a nice little metal box! And here are yet more cubic ones in nice little tins. And here's a balls-and-bars set at DealExtreme that actually comes in Buckyballs packaging, which would normally mean it's a knockoff. Now, though, it may be the real thing, being sold where the product ban cannot reach.)

Again, these prices are all excellent, and you can get the usual bulk discounts; if you decided to buy a thousand of the super-cheap tiny discs, for instance, you'd pay $US33.90 delivered for the lot - three point four cents per magnet!

When I started writing this piece, I was all fired up to mention yet again that Kinder Surprise chocolate eggs with a toy inside are banned in the USA, and they're not banned in most other places, and the confectionery aisles of Australian supermarkets are not, so far as I have been able to determine, littered with the corpses of asphyxiated children, and presumably that's because all Australian shelf-stackers know how to administer the Heimlich maneuver. I also contemplated using the term "natural selection", with regard to children over the age of ten who eat their toys.

And as I've written before, I'm not crazy about preventing grown-ups from having things that could hurt children, or other adults, if used irresponsibly. Things keep being banned if they're possibly hazardous and, in the opinion of busybodies, more fun than they are useful. This is, to use the technical term, bullshit; it's the sort of Puritan worldview that bans recreational drugs for no reason other than that they are recreational drugs.

Most sane people accept, however, that it is difficult to make a case for private ownership of land mines in the civilised world.

Or, to pick a more realistic scenario, it is fair to prohibit the construction of booby traps on your own private land to catch trespassers, because even if it is your private land, you're living in a society here, and bear-trapping firemen, punji-staking tourists who wish to ask for directions, or SM-70-ing anyone who investigates the smell after you die in your house, has been decided by the rest of us to be unacceptable.

Less theatrically again, this is why the civilised world generally requires people building and maintaining structures to do so to something approaching local code standards, because you're not the only person who's going to have to deal with the place, even if nobody else busts in there until after you've died. If you want to have deathtrap electrical wiring, giant piles of fermenting garbage and guard dogs driven insane by mistreatment, get the hell out of the First World, because we've decided we won't put up with that. There's a limit to the risk to others that you're allowed to create in the name of individualism.

And so, after yet another reduction of the drama involved, we get to little shiny toy magnets.

On the one hand, they're fun, and the number of serious medical incidents they've caused is trivially small compared with those caused by skateboards, netball or hiking.

But on the other hand, they have been demonstrated to pose a real hazard, and there's no good way to mitigate it. No amount of "keep away from ALL children" warnings will make these small shiny lose-able objects actually inaccessible or unattractive to small children, and people don't seem to take the warnings seriously anyway. And even if you've no kids and no intention to have them, the little bastards are still likely to find their way into your house at some point.

And the danger isn't just of cuts and bruises. A perforated bowel will very probably kill you if you don't get serious medical treatment, whether you're four or forty.

One way to mitigate the danger of products and activities is to require licensing or other legal paperwork before someone can buy or do whatever it is. But this is for guns and cars and SCUBA and skydiving; it's ridiculous for executive-toy novelties.

We live in a world of imperfect solutions, and upon reflection, I think bans on small magnetic novelties aren't even the least perfect solution I've seen today. Especially if it's not a Ban On All Magnets.

As long as you can still buy 10,000 round NIB magnets with the same specs as the ones sold under special brand names on eBay, or wherever, or similarly buy tons of even cheaper disc magnets for the thousand and one things they turn out to be useful for, then I don't count destruction of the market for marked-up novelty-shop (or even worse) versions of the same things to be a great injustice.

I accept that the current magnet bans are much more likely to lead to truly onerous and irrational magnet bans than, say, the acceptance of gay marriage is to lead to people marrying farm animals. If and when someone tries to ban strong magnets in general, even huge ones that pose a serious danger to grown-ups, I will stand up and be counted in opposition.

But even as a quite serious appreciator of weird and wonderful toys and gizmoes, I see no strong grounds for complaint in bans on little magnets sold as toys.