I've written often about scams, of one kind or another. I find them fascinating.

I've tied myself in knots classifying this one, though. To my mind most examples of it are clearly over the "scam" line, and I think almost everybody would agree that at least some examples of it definitely are, but...

Look. Here's the deal.

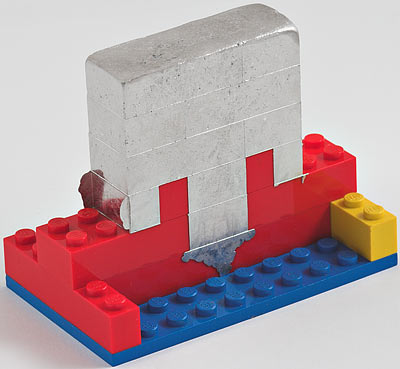

The other day, I wrote about "liquid metal bullion"...

...which was presented on eBay as some kind of investment that's fun for all the family. It's actually of some interest as a novelty, but has little monetary value and is full of poisonous heavy metals.

While exploring the peculiar world of the "liquid bullion" dealers, I discovered another odd category of eBay "bullion":

"Gold" bars and coins, that actually have very close to no gold in them.

And "silver" ones, too, and a few others plated with more exotic precious metals. But mainly gold.

I bought one. Here it is. I paid a grand total of $US2.30 for it, including delivery, from this dealer.

It took a couple of weeks longer to arrive than it should have - possibly because the sender didn't know the difference between Australia and the UK, as far as address labels go - but apart from that, the transaction was entirely unremarkable.

I was going to cut into the bar to show it wasn't solid gold, but since it sticks to a magnet, I think we can pretty much take that as read.

A metal that sticks to a magnet must contain iron, nickel and/or cobalt, iron being the cheapest. So under the plating this is clearly a slug of iron or steel of some sort.

For the sake of completeness, though, I still measured its vital statistics.

The bar's dimensions are about 44 by 28 by 3 millimetres, which would give it a volume of about 3.7 cubic centimetres if it didn't have rounded corners and that embossed image of Jesus-with-wings-for-some-reason on one side...

...and an angel and some symbolic Commandments on the other. (It also came with this little clear plastic case, to help keep the practically molecularly thin gold layer intact.)

(Oh, and yes, I did specifically choose this particular style of object-of-no-value made to appear desirable by a perfunctory shiny coating. On account of the symbolism. I'm dead subtle, me.)

When I measured the volume of the bar more accurately via the immersion method (PDF), as per the liquid "bullion", I got 3.5 cubic centimetres.

When I weighed it normally, I got 27.4 grams.

That gives a density of 7.8 grams per cubic centimetre. My lab balance and cack-handed technique are accurate enough that I'd say with some confidence that the real density is somewhere in the 7.75 to 7.85 range.

The density of pure iron is 7.9 grams per CC; various steels have densities between 7.75 and 8.05 grams per CC. Common mild steel is about 7.85.

So yeah, this is indeed a chunk of cheap steel, as any fool who stuck a magnet to it could have told you without all the science stuff.

At this point you might be thinking, "No harm, no foul". It looks like gold, but it doesn't feel like gold or in any way beyond superficial appearance attempt to resemble gold. So it's just a decorative trinket, not an attempted scam. Right?

Well, maybe. Except the auction title was:

HOT EXTREMELY RARE!! "Jesus"_1 Troy oz. .999 24K Pure Gold Layered Bullion Bar

Let that sink in for a moment.

As I write this, the same seller has more bars just like this one, plus other ones with these descriptions:

Amazing price MAPLE LEAF GOLD BAR One Troy oz 100 MILLS .999 Gold 24K PLATED

NR! 1 OZ GERMAN 999 PURE 24K GOLD CLAD 3RD REICH IRON WWI WWII BULLION BAR!

1 oz 24K GOLD plated elephant OF SOUTH AFRICA the Krugerrand BAR 100 Mills RARE

NEW ITEM! 1 OZ. SOVIET RUSSIAN USSR CCCP PURE .999 24K GOLD LAYERED COIN BAR NR!

...and so on.

All of the descriptions contain keywords you'll find in auctions of solid-gold items, but some of them also have the plain words "plated", and "gold clad ... iron". Others, though, only reveal their not-anything-like-solid-gold nature with odd terms like "100 Mills" or "gold layered".

Both of these terms seem to be recent inventions, at least when it comes to bullion. By definition, there's no such thing as "plated bullion"; it's as silly, though not as hazardous to health, as calling that low-melting-point alloy that has lead and cadmium in it "non-toxic".

EBay currently has quite a lot of allegedly-bullion items using these odd descriptions.

There actually is a unit called a "mil", with one L instead of two; it's a thousandth of an inch. That's obviously not what it means here, though, because a hundred mils is a tenth of an inch, which is 2.54 millimetres. If you can figure out a way to make something that's three millimetres thick yet plated with 2.54 millimetres of gold on both sides, a career as a TARDIS engineer awaits you.

What "mill" actually means to the eBay gold-plated bar-and-coin sellers is... unclear. Perhaps it's a millionth of an inch. A hundred millionths of an inch is 0.00254 millimetres, 2.54 microns; that actually does qualify per the US Federal Trade Commission as "Heavy Gold Electroplated". You can get thicker plating that that, too, up to the point where it qualifies as gold-filled, with the gold accounting for a readily measurable fraction of the item's weight, rather than just a barely-weighable plating. (Apparently a general rule of thumb for jewellery subject to wear is that one micron of plate thickness will wear off the item per year.)

Given that the "mill" is not any kind of defined unit and seems to be interchangeable with the similarly un-defined "gold layered", though, I don't think it's excessively uncharitable to assume that the actual thickness of the plating on these things is as thin as possible without letting the colour of the underlying metal show through.

I mean, the one I bought is supposed to be "1 Troy oz", too, but it only weighs 27.4 grams, not the 31.1 grams of an actual troy ounce. It doesn't even quite make it to an ordinary avoirdupois ounce; that's 28.35 grams. Given gross failures like this, I doubt the vendors spend a lot of time worrying about the actual thickness of their plating.

But so what, I hear you say. This is just the usual level of cheerful eBay flea-market dodginess, right? Anybody who's been on eBay for a while is probably familiar with its own special not-quite-scams.

Listings, for instance, that don't make it quite as clear as they might that the item being sold is an empty box which at one point contained the new and exciting game console prominently featured in the listing title. See also people selling a picture of a fancy guitar, or a miniature dollhouse version of a big-screen TV. Et cetera. If the buyer cannot figure out why a "one ounce" gold bar is selling for $2.30, wasting money on eBay is probably not their biggest problem.

I invite you, at this juncture, to check out the highest prices people have paid for "100 mills" or "gold layered" things on eBay, by searching completed listings. Red numbers indicate something that didn't sell, green numbers indicate a sale.

As I write this, that search is headed by "1 OZ GOLD SOUTH AFRICAN 2010 KRUGERRAND COIN BULLION 100 MILLS 999.9 24K LOT 10", which a UK seller unloaded for £670 ex delivery - more than a thousand US dollars.

Those were clearly not real Kruggerands, because the listing says: "This 2010 coin is layered with 100 mills thick of pure 24k Gold". But right before that, the listing copies from Wikipedia and says, "The Krugerrand is a South African Gold Coin, first minted in 1967 to help promote South African Gold. The coin, Produced by the South African Mint, proved popular and by 1980 the Krugerrand accounted for 90% of the global coin market".

Which is true. But those solid gold coins are not what this dealer is selling. They are selling ten coins that look a bit like them, but are each worth no more than my little plated Jesus-bar.

Unquestionably, the person who paid £677.95 delivered for these ten shiny poker chips was under the impression that they'd just bought ten ounces of highly fungible gold at a huge discount.

They are not alone in this thought. Scrolling down that search turns up a ten-gram "100 Mills" bar that sold for a hundred UK pounds, then a five-gram "100 Mills" bar selling here in Australia for $AU122.50, then a five-gram "100 Mills" bar from an Irish dealer selling for €87.50.

Four "2010 UK SOVEREIGN COINS -1oz - 24k PURE GOLD Layered .999 Fine -TAX FREE"? Those had "100 Mills" in the description, and went for £159.90 delivered. Another seller was pleased to relieve a customer of £154.94 delivered for "NEW 2013 Royal Coronation & 2012 Jubilee 24k PURE GOLD Layered Double Coin Set", again allegedly "100 mill" plated and "Genuine Coins - Not Copies Or Reproductions"!

That same seller also managed to unload a single "2010 BRITISH SOVEREIGN 24K PURE GOLD Layered Proof COIN -1oz .999 Fine *MUST SEE", for £106.99 delivered.

And on and on it goes.

So: Is this a scam?

I'd say yes, because "good faith" is a critical legal concept. Good-faith, as I've written before, is the undoing of a long list of "technically legal" rip-offs. If there is no way anybody would agree to a given deal if they knew exactly what it was, then camouflaging the true nature of that deal, however lightly, is attempted fraud.

Deals of this nature are, of course, not hard to find, and they're often being offered by large corporations, not eBay fly-by-nights. Payday-loan shops, dodgy mechanics, questionable sweepstakes, and umpteen outfits whose business model seems to accept a repeat-business level below one per cent and the kind of word-of-mouth goodwill usually only enjoyed by serial killers.

What about rebate programs that require you to send the same cut-out barcode from a package to two different addresses simultaneously? Reward-points programs predicated upon normal consumers' points expiring before they accumulate enough to be able to redeem them for anything? Airlines that routinely sell more tickets than there are seats on the plane, in the expectation that not everybody will actually get there on time (thanks, interminable "security" nonsense!)? And, of course, the worst invention in the history of capitalism, gift certificates, whose principal reason for existence is "breakage", that portion of the gift cards sold which are never redeemed.

There's plenty of other underhanded activity in the bullion market, too, with the endless promotion of overpriced "collectible" bullion coins (particularly to certain market segments...), and sharp dealing in the "cash for gold" business. But at least all of those outfits generally are selling and buying actual gold, not plated slugs that only superficially resemble actual bullion.

Advertising a near-worthless little chip of gilded steel as "Gold Bar 5 Grams 'Canadian Maple' 100 MILLS .999 24k Fine Bullion!" is not a good-faith act. You're clearly fishing for suckers.

There are some other murky terms used in describing these bullion-like shiny objects. "HGE", for "heavy gold electroplate", for instance, which is a term that exists in the jewelry market, but not so much in the bullion one. And "gold dipped", suggesting there's some worker out there spending all day dunking Krugerrand-resembling circles of steel in a cauldron of molten gold. There's "thick layer", too, which I think always indicates a layer actually notable for its thin-ness.

This rather cumbersome eBay search is for several of these terms, but not the slight-honesty-indicating terms "not pure gold", "not 100% solid gold" or "not solid gold". It has plenty of hits even when it's only searching the titles, and hundreds of hits if you click the little "Include description" box and then click Search again.

People sometimes pay big bucks even for the eBay items whose listings do include "not solid gold" disclaimers, though. And everybody who buys one of these things for more than the couple of bucks it's worth should have paid more attention. There's almost always some clue, if only what turns up when you search for terms like "gold layered" or "100 mills".

But not everybody is able to pay more attention, or aware of just how many scams there are on eBay.

I would also be willing to bet, given the long and depressing list of large green numbers in a completed-listings search for this gold-plated tat, that some people have spent a lot of money on these things. Perhaps they're hoping to quickly flip this amazing bargain to local precious-metal dealers. Perhaps they're under the impression that they're providing for their childrens' future. All they're actually doing, though, is transferring their life savings to a person selling scrap iron, and possibly lining themselves up for criminal charges if they ever try to sell these damn things on.

Not everybody selling gold-plated imitation bullion is a scumbag. Some of the "gold layered" listings are fixed-price "Buy It Now" items, for instance. Those cost a few bucks more than the auctioned ones usually sell for, but by their very existence they provide a strong clue that both they and their auctioned cousins aren't what your slightly dotty grandparent with an iPad and time on their hands might at first assume them to be.

Someone could still blow their entire retirement nest egg on the Buy-It-Now ones, but it'd take some effort. And the buyer would at least end up with a really big pile of almost worthless gold-plated novelties, which'd look good in an outraged local news story.

Some of these things also have pretty-much-honest descriptions, that clearly say something like "plated" or "replica" instead of "dipped" or "layered" or whatever. (The one I bought may not have put any disclaimers in the title, but its description text did contain "*PLEASE REMEMBER THESE BARS ARE NOT SOLID GOLD*".)

Even these better dealers do still love the magic word "bullion", but they're nonetheless more or less in "good-faith" territory, if you ask me. Even a moron in a hurry might realise the product is not solid gold when it says "plated" right in the auction title.

Oh, and just to confuse things even more, you can get real silver coins and bars that've been "layered" with gold. People overpay for those, too. As I write this, a Completed Listings search shows that someone thought a "2000 Washington Mint Sacagawea 24kt Gold Layered .99 Silver 4 Troy Oz Coin" was worth $US167.49 delivered. The gold value of that coin is as usual negligible, but presuming the seller's telling the truth about the amount of silver in it, then it is at current spot prices worth about eighty bucks.

So, still a rip-off, but only by about a factor of two.

("Silver-gilt" items are quite common in the legitimate jewelery business, especially for large items like sculptures and medals. Olympic "gold" medals, for instance, are silver-gilt to keep the price down. By specification they have to be be at least 60 by three millimetres, which at 2014 gold prices would make them cost the thick end of seven thousand dollars. There are more than three hundred events in a Summer Olympics and another hundred in the Winter, so that'd add up, especially for larger-than-spec medals; the London 2012 medals were unusually large, at 85 by 7mm. That much solid gold is currently worth well north of $30,000. So instead, Olympic golds are silver with a generous six-or-more grams of gold plated onto it, to make sure that even if the medal-winner insists on wearing the thing around all day, it won't wear through the plating.)

As I write this, a Completed Listings search for these gold-plated silver coins shows only six sold going back to May this year. The least anybody paid for one was $US105 delivered. For a coin worth, I remind you, $80. And that only when you manage to find someone who'll listen to your story about how there really is some silver there under the silly gold plating.

(This problem may solve itself, because very thin gold plated straight on top of silver will slowly turn silver and tarnish as silver atoms migrate through the gold. To avoid this, "proper" gold-plated silver jewellery has "barrier layers" in between, in a sandwich that may be silver, then copper, then nickel, then finally the gold. I doubt the sellers of "gold layered" "100 mills" silver coins go to these lengths to make sure their products retain their lustre.)

High in the most-expensive-first Completed Listings searches you'll also find a number of people paying a few hundred dollars for one hundred plated coins or ingots. Those people have not been ripped off either, though I presume most of them are hoping to get in on this occasionally-lucrative business themselves.

Please don't do that.

If you appreciate kitsch, do feel free to decorate your wall with the complete series of ULTRA RARE SOVIET NAZI JESUS ELEPHANT LUCKY MONKEY MARTIAN GOLD LAYERED ALMOST AN OUNCE HYPERBULLION INGOTS.

But I wouldn't pay more than two bucks a unit, if I were you.