A while ago, I reviewed a book with a lot of fictional death in it. I didn't like that book much.

Today, a book with a lot of factual death in it. I like this book a lot.

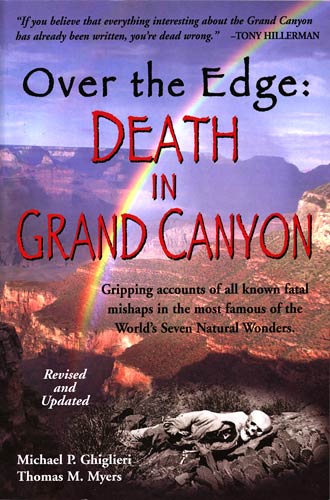

Over The Edge: Death In Grand Canyon, by Michael P. Ghiglieri and Thomas M. Myers, is accurately titled. It chronicles the numerous ways in which people can end, and have ended, their lives in Arizona's Grand Canyon and its environs.

There are a lot of deaths in this book. A lot of deaths. The means of death that sprang first to my mind when I discovered the book existed was people larking around pretending to step off the edge, and then not pretending quite so much. And yes, those people are in there. But so are underprepared hikers, plane crashes, an awful lot of people in boats, and gruelling tales of historical exploration.

Every now and then a tale in Over The Edge ends with someone surviving. But that's really not the way to bet.

Absolutely the worst thing about this book is the cover. It clearly depicts a rainbow-farting unicorn plunging to certain doom, so that's good, but it's got that weird "undesigned" look typical of self-published crank-screeds. (And, yes, it's also got Papyrus, again.)

And, while I'm whinging, the editing and proofing isn't everything it might have been. There are occasional typoes, like two different renditions of someone's name, not to mention uninventive prose like "a deadly game of Russian roulette" - as opposed, presumably, to Russian roulette played with a Nerf revolver.

And, if I'm honest, the middle of the book's not as fascinating as the beginning. The middle's where you'll find numerous deaths in modern river-runs, usually because of lousy steering by boatmen, and other stuff that could pretty much happen anywhere - air accidents, freak accidents, (a surprisingly small number of) suicides, and murders.

(I did find an unfortunate interaction between a low-flying helicopter and an environmental sediment-transport study to be blackly hilarious.)

But perhaps I'm being too demanding. People wind up dead at a regular pace throughout the book, which really should be good enough for me. And there's quite a bit of variety; it's not all "If you choose to play a practical joke on your young daughter by pretending, with great theatricality, to fall off the edge of a canyon and hundreds of feet to your death, it is a good idea to make sure that the ledge just below the edge on which you intend to land is not covered with loose pebbles forming a slope at their critical angle of repose."

To extract maximum entertainment from this volume, you may by this point have figured out that you need a somewhat morbid sense of humour. Watching Dad leap off the edge may be a horror beyond imagining for the onlooking mum and kids, but if, like me, your first thought on seeing that the man in question actually did have kids was "darn, not eligible for a Darwin Award, then", you're all set to enjoy the rest of the volume.

All this is not to say that this is one of those schlocky publications aimed at People Who Like Football, and Porno, and Books About War. Over The Edge isn't relentlessly po-faced, but neither is it buckets-of-blood-narrated-by-Jeremy-Clarkson. It does help if, like me, you decided to download the coroner's report linked from here specifically because of the warning about the photos it contains (and then, like me, decided that the term "extensively morselized" made the document a must-read all by itself...), but Over The Edge is really a collection of true stories of people in horrible situations, and the noble, venal, foolish and/or altruistic things they then do.

It also, definitely, has educational value. I now, for instance, know some more of the wonderful panoply of ways in which whitewater can murder you, whether the flow rate is high or low.

High rates give deeper, and possibly also faster, water, which in the case of the Colorado River may be startlingly cold (Over The Edge's co-author thinks this may be because of the Glen Canyon Dam, which releases water from its ice-cold depths, not its warmer surface). Low flow rates are still often plenty to whip your feet out unexpectedly from under you (people keep forgetting that a cubic metre of water weighs a tonne, and even a mere cubic foot of water weighs more than 28 kilograms {62 pounds}...), and they also make rapids much rockier, and thus more likely to break your boat and then your body.

Many of the deaths in Over The Edge are quite improbable. Horsing around on the rim of a canyon, or going for a hike in the heat equipped with a Snickers bar and a 591-millilitre bottle of Dasani (and not even telling anyone you're going...), are both dangerous activities. But people do these sorts of dumb things all the time, and the overwhelming majority of them survive. Often without even having to involve rescue staff (also known as the TNS, or Thwarting Natural Selection, Squad).

Over The Edge can be quite educational, though, in showing you how to avoid taking less obvious risks, even if you're never going to visit the Grand Canyon. Much of the advice is highly applicable to any backcountry adventuring, especially in gully country.

For instance: Yes, lost people really do have a strong tendency to walk in circles, even when they should be able to get their bearings from their surroundings.

Oh, and if you're going out on the water, or just wading into the water, or possibly even just fishing in the water from the shore, WEAR A LIFE JACKET.

And, advice almost as important, if more specialised: If you have a history of sleepwalking, don't camp right next to a river.

(The poor kid starring in that particular story was meant to be camped miles away from the river, but the adult leading the trip got the group stranded next to the river for the night, when they got there too late and the one flashlight the adult brought didn't work.)

You also, it turns out, can't count on arid country having the traditional desert climate where it's hot during the day and freezing cold at night. The Canyon manages to stay hot right through the night! Enjoy!

And young, fit people - especially children - can become severely dehydrated while they're still running around and looking chirpy enough. Then they suddenly crash, and five minutes later their heart is still beating, but there's windblown sand accumulating on their unblinking eyes.

And, remember, kids: Just Say No to jimsonweed. Seriously.

And then there are the historic stories, featuring numerous explorers who figured that God would not have made a place so dismal and lethal as this without putting at least one damn good vein of silver in there somewhere.

(This reminds me of the fact that for a lot of people in the olden days, forests, canyons and mountains were not "beautiful". Ships, bridges, castles, cathedrals and geometrically landscaped gardens were beautiful. It was only when we started to have the luxury of not having to look at nature all the time that we started finding it appealing.)

The central theme of this book is that wilderness does still exist, and does not automatically come with handrails and warning signs.

I'm quite close to some wilderness myself. I live in Katoomba, New South Wales, and my house is a lazy ten-minute walk from Echo Point. At Echo Point itself and most of the cliff walks around it, you do get a pretty good supply of handrails and warning signs, and people almost never die, except occasionally on purpose.

Tromp on down the Giant Stairway into the rainforest-y valley, though, and things change. The valley barely qualifies as a pothole compared with the Grand Canyon, and most tourists just toddle along the wood-paved walkways and catch a cable car back up. But if you strike out south you're instantly in a heavily-forested National Park. People can and do get life-threateningly lost down there, even after so little wandering that if the land were magically flattened they could walk to a place that serves a really good latte in about an hour.

I thought Over The Edge would just be morbid, shading to morbidly-hilarious, which would be good enough for me. But it isn't. Yes, it's basically just a long list of people who died, almost died and/or really should have died (serious Survival Bonus Points, for example, go to the immobilised-by-injury woman who managed to catch the attention of people hundreds of feet away by shouting, even though she had two collapsed lungs...). But it's frequently fascinating.

And, of course, if you're actually going to the Grand Canyon, to do anything more than stand 30 yards from the edge under a parasol, there is no better book to read beforehand. And to be seen reading while you're there.

Recommended.

(Buy it at Amazon, and I'll get a cut!)

, the first book in that series, written slightly before Futurama debuted and so forgivable for its inclusion of a captain named Brannigan.